Cheyenne Richards

The Prisoner's Apprentice

The Prisoner's Apprentice

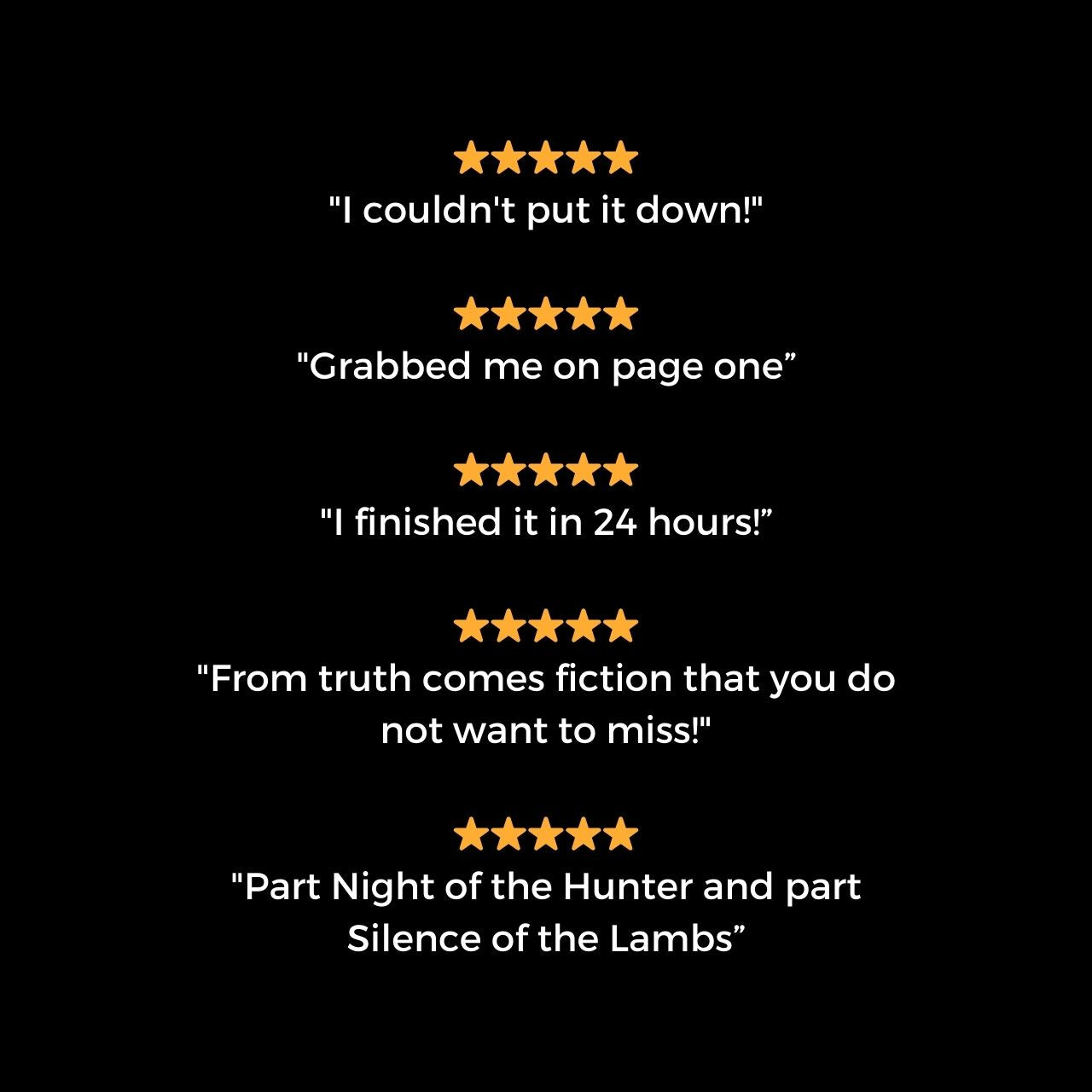

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ 58+ 5-Star Reviews

Couldn't load pickup availability

FOR E-BOOKS & AUDIOBOOKS

- Buy Book

- Download to Kindle, Phone, or Tablet

- Enjoy!

FOR PAPERBACKS

- Buy Book

- Shipped in 1-3 days

- Enjoy!

Synopsis

Synopsis

As a weakling in a frontier-toughened town, young Albert Jarvis is relentlessly denied his only desire—a hint of love from his stone-hearted Pa. Then a captivating stranger, accused of heinous crimes, gets shackled in his father's jail and promises Albert a spellbinding future of achievement and acceptance.

When a shocking betrayal forces Albert to make an impossible choice, he lands on the unforgiving streets of Manhattan on the edge of survival. With only his unreliable mentor as a guide, he struggles with grueling poverty, glittering ill-gotten wealth, and cruel deception—until his teacher crosses an unthinkable line.

Now caught in a dangerous test of loyalty and treachery, Albert must prove himself worth his salt, or lose something far worse than his life in the gripping psychological thriller.

Inspired by the true story that rocked the 19th-century world, this unputdownable novel is a must-read for fans of The Alienist, Oliver Twist, and Devil in the White City. The Prisoner’s Apprentice won the 2022 IRDA Historical Fiction Award, was a finalist for the Eric Hoffer Historical Fiction Award, and was awarded an Indie B.R.A.G. Medallion.

Chapter One Look Inside

Chapter One Look Inside

That sweltering June began like any other. A few fighters and a buggy thief flowed through our jail. A man from the plaster company married a girl from Dryden. Eph Schutt lost his wife and baby to childbed fever. Mostly I remember the endless funeral sermon and Eph’s sister giving me a hard smack on the shoulder for kicking at the pews.

By the Fourth of July, everyone with a boat was out on Cayuga Lake, dragging chains and hooks and fishing nets, looking for bodies.

Each had a theory about where Rulloff might have dumped the remains of his missing wife and child—poor Eph’s sister and niece—but their chaotic searches led nowhere. The Independence Day parade that year looked more like a funeral march, with both the Friends of the Ithaca Railroad and the Anti-Slavery Society cancelling their lectures out of respect for unprecedented circumstances.

I was only six then, but as far as I can decipher, Edward Rulloff had once held a reasonable reputation in Ithaca, though always that of an outsider. I must have heard his name in passing, but had never met the man. He’d been a teacher for a while, but school cost a fortune in those days, even if Pa had believed in scholarship, which he most fervently did not. Later, Rulloff practiced herbal medicine, but again, paying for a doctor was not in Pa’s perspective of how the world should run.

With my help, Rulloff would soon build a far more impressive résumé: doctor, lawyer, professor, inventor, philologist fluent in twenty-seven languages, serial killer.

As the summer dragged on, voices grew more hushed. Mothers held their children closer in the folds of their skirts, and vague dread pulled at the whole town like an undertow.

Each time a rope went down, I wondered if they would pull a waterlogged baby from under the glassy surface. I was still a novice to death then, but learning fast. The boy down the street told me dead people’s eyelids fall open forever, that’s how you know they’re dead. I wondered if somewhere in the lake the lady and her baby stared at each other with wide eyes, never blinking. I tried to imagine it by leaving my eyes open but couldn’t do it. The air was too dry, the sun too bright.

In those days, Pa and I headed to Grant’s every night for supper. The sign said “Grant’s Coffee Shop” to appease the pastor, but they only served whiskey and women. And while that time is fuzzy in my memory compared to what happened later, I knew there were three things I could always count on when we walked through that sloped doorway.

First, someone would have saved Pa’s table, the best one in the place—closest to the south window. In the summer, the breeze carried the cool freshness of the lake in through that opening. The table was easy to spot—blackened on one leg from being used as a fireplace poker. There weren’t enough chairs, so I was always relegated to the warped floorboards and took care to position myself as far as I could from both the spittoon and the older boys who stole my bread and marmalade.

Second, the men would talk longer than I could stay awake. Pa was officially Ithaca’s jail-keep, but unofficially more like the mayor of our little village, leading talk on whether the Peterson land was too shaded for apples and who’d been lost over the winter to the blizzard, the pox, or buggy accidents. Gradually, travelers would pull one chair after another in his direction until Pa sat in the center of a big circle, each stranger in turn buying a half-pint to pass around. A patent medicine man would tell of a brush with bandits on the road, a boat hand of an explosion that lit up the whole Hudson, a circuit lawyer of Indian attacks in the territories. Or else there’d be a trapper with stories of giant bears chasing him through the woods. Or a logger who showed off his scars. And as the oil lamp’s shadows danced over the bare plank walls, I learned by installments that my home town was meager and insignificant, and that the world outside was impossibly vast and full of adventure.

And third, after several rounds, someone would nudge me awake to remind me that before I was born, my fearless father had rushed into a blazing house and saved a whole family from a fire all by himself—the parents, five kids, and someone’s cousin. Then every soul in Grant’s would toast Pa, down the rest of the whiskey and sing “There Is No Home Like Mine Own” good and loud and stumbly.

I’d once asked Pa how I could become brave like him.

“It’s in your blood, Albert. Your grandpa died fighting the Creeks. His pa marched with Sullivan. You’ll grow out of this namby-pamby phase and become a man worth his salt. I’ll make sure of it.”

I wanted to believe him, but I could never shake a nagging certainty that instead of a hero like Pa, I was destined to become the family coward. For all Pa’s encouragement to face down the bullies, I only learned how to run. And the day Pa tried to teach me to swim, he tossed me in the lake and I choked and coughed and windmilled my arms till he had to plunge in with his boots on and pull me out himself.

After, I clung to Aunt Babe’s leg.

“You can’t terrify a child like that,” she snapped.

“How the hell you think I ever learned?” Pa’d yelled right back.

All this, of course, was before the nightmares about dead babies began.

Eph, still in mourning clothes for his wife and baby, had trudged into the jail and told Pa he was worried because now his sister and niece were missing. Mostly I remember feeling secretly avenged, thinking about that smack she’d given me, until the catch in his voice drenched me in shame. He was a big man, but his back trembled as he told Pa there was no sign of Harriet, baby Priscilla, or Doc Rulloff. At the house, Eph said, he’d found dishes caked in food and laundry strewn across the floor.

Pa’d told Eph not to worry, Rulloff had probably taken them for an afternoon row on the lake. Surely, they’d be back by nightfall.

“Awful things grief can do to the mind,” he said to me later. “No one needs tell me. Terrible thing to lose a wife in childbirth.”

Three weeks later, Eph’s sister and niece were still missing. Pa had to call the sheriff in from Elmira, and that’s when things started to happen quickly. They discovered Rulloff had fled and tracked his movements as far as Syracuse by stage, but lost his trail at the canal. The sheriff brought in hounds to scour the acres around Rulloff’s house, but found no sign of hastily dug graves.

I heard speculations around the water pump, not meant for my ears but not whispered either. The brewer’s wife told the Clinton House cook that they’d found disemboweled animals in Rulloff’s cellar. The tanner said bodies don’t stay underwater forever. Eventually, they rot and pop to the surface. He knew because he’d lived in New York City once, and bodies were always floating on the East River there.

For all the lake dragging, no one could find the bodies of Eph’s sister or niece, but someone recalled that Eph’s wife and daughter had been doctored by Rulloff just before they died. Suddenly, the question swept through Ithaca like a chill wind—had they actually been taken by fever, or had Rulloff killed all four of Eph’s kin?

A week later, a different doc from Dryden was brought in to exhume the remains of Eph’s wife and baby—the only two bodies they did have. With all the newfound bloodlust, I remember feeling disappointed that he couldn’t say for sure whether they’d been killed on purpose, only that he found copper in their bellies. Copper wasn’t part of any cure he knew of, but he only knew medicine from Gunn’s book. As a test, he tried feeding copper to a rabbit. The rabbit died.

That was good enough for the locals, and soon every conversation—at the Saturday market, in the lanes, at church—became an urgent cry to find and hang the dreadful monster who’d committed such abominable acts against innocent women and children. In my imagination, Rulloff grew into a half-man, half-growling beast, covered in blood, with stooped shoulders and wolflike hair.

Every night I endured nightmares of meeting Rulloff alone in the woods, but in the real world, there was no word of him for weeks. The jail sat empty, so Pa kept me busy planting carrots, digging turnips, and piling wood for the kitchen fire. Meanwhile, Pa got new shoes for the horses and greased the coach axles and cleaned his gun, but although he sent urgent telegrams to all corners of the state, the replies came back with no new information.

Until one oppressively hot afternoon in early August.

Share